From April 3-9th, I will be leading a retreat on the Big Island called Pele’s Fire. (For those of you in Hawaii, and therefore on Hawaiian time, if you are interested in joining us for one day only, we have an Aloha Friday intensive that you can still register for here. As we planned this, one of our participants, Heather Leah Huddleston, asked us some questions, which I share with you now. I hope all you writers find some inspiration!

From April 3-9th, I will be leading a retreat on the Big Island called Pele’s Fire. (For those of you in Hawaii, and therefore on Hawaiian time, if you are interested in joining us for one day only, we have an Aloha Friday intensive that you can still register for here. As we planned this, one of our participants, Heather Leah Huddleston, asked us some questions, which I share with you now. I hope all you writers find some inspiration!

“…for me, the word ‘core’ feels like I am in partnership with my work…” ~ Elena Georgiou

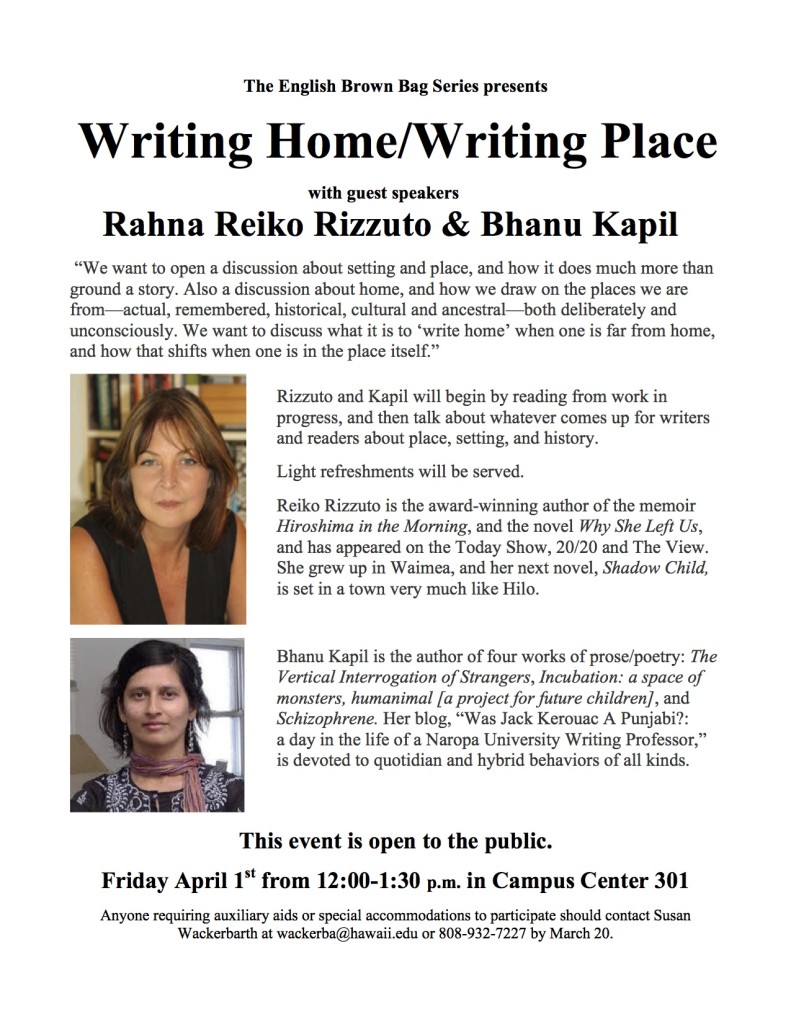

Pele’s Fire was birthed from the very core—hearts, minds, passions, and desires—of three women: Rahna Reiko Rizzuto, Elena Georgiou and Bhanu Kapil. Joined by Black Belt Nia instructor Susan Tate, who will incorporate daily creative movement classes, including Nia, these mentors make Pele’s Fire the retreat to access, to transmute, to move and write from the core of the body, from the very core of our planet.

One may think: Why Hawaii? Why movement? Why writing? Here’s what the leaders of Pele’s Fire have to say about the importance of accessing your words (and your work) from the core of who you are….

HLH: What is at the core of the offering?

REIKO: The writers are at the core. We have designed the retreat to feed, nurture and inspire them in every possible way. Feeling stuck and need some exercises and brainstorming? Check. Want a small group to read your work, and a one-on-one conversation that dives into the problems, possibilities and strengths of your manuscript? We got you. Want to dance all day, or not at all? Your choice. Looking for a community to immerse yourself in, or intense quiet where you can write the day away? You can have that too. And more.

My point, though, is that everyone writes differently, learns differently; each one of us is coming from a different place, with different needs. So what we are offering is an open hand and a refuge. It’s an approach I learned from Hedgebrook, the retreat for women writers on Whidbey Island. They call it “radical hospitality.” And it is rooted in the belief that every writer’s voice is important, that we are the authors of change. At Pele’s Fire, our “core” is to nurture the writer, nurture the voice, nurture the change.

HLH: Why Hawaii?

REIKO: Hawaii is my home. I was born there and grew up with the rhythms in my blood. I think each of us is imprinted by the sounds and smells, the air, the land and seacape of the place where we were born—so perhaps I am biased—but, for me, there is an energy in Hawaii that offers great peace and inspiration. I wanted to help open a door—not to the touristy “pina coladas on the beach” Hawaii, but to the vital energy of a land that is literally regenerating itself, and to the aloha spirit that I feel our troubled world could use a whole lot more of.

“In the stillness of retreat, we can hear our part, our ability to change the melody, rather than trying to jump in and follow a prescribed lyric. What we write—or do not write—contributes to the symphony that is our culture, our humanity, our future.” ~ Rahna Reiko Rizzuto

HLH: Place definitely has spirit. The earth is always humming. When we connect to the body and the words, that hum is what moves us. What happens when we get stuck—either physically or in the work? Do you think moving one will automatically free the other?

BHANU: The word that comes to mind is from Lauren Berlant: “receptivity.” How can we receive that “hum” up through our legs, into the middle of us? Retreat settings are always, in my experience, about someone—the person who dreamed/built the retreat center, I suppose—having been very thoughtful about the site, and the energy of site. Kalani feels like this kind of place to me. There is something already there that we can connect to. What does it mean to connect with the energy of land that has a strong indigenous history? I know that I am very conscious of this in Himalayan spaces, and so want to make anything I am saying about the earth—a part of the earth I am not from—a way of honoring the invitation to be there at all. This is my precursor, you could say, to receiving the hum. What are the ethics of receiving or opening to earth energy, in a part of the earth—the planet—where we don’t have cultural connections? I live in the Western U.S., and so—walking in the Rockies and the foothills, the places where the surge of the High Plains meets the energy of the mountains—I know this, too. These are immigrant questions, perhaps. I know that part of Kalani’s mission is a deep honoring of native community and local economy, and so I feel that I am stepping into a space that is thoughtful about this. And then, having stepped over the boundary? Into Kalani? My dream is that a rigid way of being might be: interrupted. To see what happens when we begin to move. I know this from my home life—walking, yoga, pilgrimage—and trust that the same thing will happen when we are there, amplified by community, by the ones we are with and the integral “hum” of this incredibly powerful landscape. How might vibration and movement dissolve blocks to writing, but also—open: new corridors and pathways: through the strata: of our imaginations?!! What will it take to break through? Break through, that is, to our capacity to “grieve and dream.” Here I am quoting a former Goddard College student, Sayra Pinto, who I met when she was a student in the MFA program that Elena, Reiko and I teach in in another part of life. Sayra Pinto: “Our ancestors need us to grieve for them, but they need us to dream for them, too. One or the other is not enough. We need to grieve and dream at the same time.” This is what comes to mind when I think of the part of this question that is about freedom. To be free enough: to feel. To feel these things—the grieving and dreaming—in our very cells. Then to write from this cellular: place. This part of us—that reorganizes itself—and is oxygenated, you could say—by movement practices. To open. And thus to receive: the hum.

HLH: Why did you decide to incorporate movement into a writing retreat? How will getting into the body help to get into the body of work?

REIKO: Nia is a movement practice that supports many things: joy, health and balance among them. It is both completely free, inclusive and nonjudgmental, and also quite scientific. Susan Tate, our Nia guide, is the author of four books herself, and has a lot of experience with tapping one’s creative potential through Nia and movement. Dancing with her is joyful and liberating! She’s ideally suited to help us connect the body and mind, and she’ll be leading daily Nia and other offering according to whatever feels right for the writers and the day.

As for why, I think sometimes we writers get too lost in our heads. Carpal tunnel, hunched shoulders, a stiff neck—physical ailments are one type of consequence, but our writing itself can lose its power when we rely on intellect and our mind’s eye. Last year, in Ruth Ozeki’s meditation class at Goddard College, she reminded us how grounding into our bodies and connecting with sensation and emotion can help create surprising and resonant images on the page. Then there is the need for writers to locate trauma and truth in our bodies in order to connect to some of our more difficult stories with authenticity.

But there is the flip side too: not starting with the mind, but with the body. In Nia, there is a concept called “dancing through life.” It’s a way of experiencing everything as dance: laundry, eating, work, and writing. Giving the physical body its space to express, move and align often brings epiphanies into the body of work instinctively and with ease.

“Because this is a setting that is also about healing and movement in another way, I would hope that participants have an opportunity…to discharge or dislodge any blocks to writing, to the creative process or practice as it stands.” ~ Bhanu Kapil

HLH: What can one learn about the body from writing the word?

ELENA: Everything that we write begins from the body, and so I believe it is the body that teaches us to find the words—the image appears in the mind, the pen is taken up by the hand, the keyboard is pressed. All this bodily action to record what the eye has observed and the heart has felt is put to work by what and how we write. But when we talk about the body, we must also talk about the soul because it is the soul that has secreted the body, and we have to pay our respects to the soul for having a body at all. So to answer your question: What can one learn about the body from writing the word? One of the things we can learn is that movement—typing, spinning, writing, leaping—is prayer.

HLH: Music is at the core of Nia, can you speak to the music of writing—what moves it—and also what does the stillness or silence offer the practice?

REIKO: To me writing is voice, and our novels, memoir, poetry, essays are our song. Increasingly, I have been thinking about how important that is in our world: both that we join in and sing melody lines that others have started, so they know they are not alone, and also that we sing into the gaps, because there are so many gaps, so many stories that have been silenced and that need to be heard.

In the stillness of retreat, we can hear our part, our ability to change the melody, rather than trying to jump in and follow a prescribed lyric. What we write or do not write contributes to the symphony that is our culture, our humanity, our future.

On a practical level, the notion of writing as song helps me think in terms of emotion and intention when I am writing. What do I need to say? What needs to be preserved, shared, released? What is that irresistible melody running through my head? It’s beneficial to the process of writing too: bass lines, minor keys, canons, leitmotifs—these help me think about subtext, and structural metaphor, crises and momentum, all very practical tools in the transformation of life into art.

HLH: Can you speak to the volcano, the living core of the earth near the retreat center? It seems to be a place where the earth opens up, like a wound on the body. What happens when we get to the core of our work? And how can we access it?

ELENA: Writers carry their own volcanoes beneath their skin. We each have at least one. We know it’s there. We know it will erupt at some point. In fact, many pray for this eruption to happen frequently. I suppose I can speak to the volcano, but that is not the usual relationship—usually the volcano speaks to me. It often erupts while I’m driving, which is obviously dangerous—trying to drive with lava running over your thighs has proven hazardous on more than one occasion, so I’ve learned to pull over and whip out the paper and pen to put out the fire. Over the years, I’ve learned that the lava that erupts from my core is something to be revered. Not feared. Yes, we can call it a wound—so many have e.g. “we write from the wound” (Jeanette Winterson)—I’m not arguing against this; I’m just saying that, for me, the word “core” feels like I’m in partnership with my work, rather than being led by something called a “wound.” I’m not saying I want to be in charge; I’m just saying I’m a little less injured and a little more intact. When we get to the core of our work, we get to feel whole, even if that feeling is often fleeting. To access the core, we need to sit down and pick up a pen, a pencil, a computer…but sometimes to access our core, the thing to pick up is a book. And read.

HLH: Ultimately, what are you hoping participants take home with them from the retreat?

BHANU: Writing that has moved through a depth or charge process. That something in the work that was not moving, that was somehow dormant: has released a new energy into the text. I want, for each person who attends the retreat, a glimpse of that. But perhaps the glimpse is also a vision. Of what the work could really be. Because this is a setting that is also about healing and movement in another way, I would hope that participants have an opportunity—through the Nia offering (which I am very excited about as someone who is new to Nia this year, or the yoga, or walking itself)—to discharge or dislodge any blocks to writing, to the creative process or practice as it stands. Is it possible to take home the knowledge we have at the end of a pilgrimage? I remember feeling this at the end of a pilgrimage I made in the Himalayas last fall, a pilgrimage that was also about writing. I felt as if I had to command myself to remember! And, indeed, upon my return to the U.S., part of what happened was the work of sustaining and recollecting what felt so clear when I was: in that other place. So, I hope that participants leave with a different time in their bodies, the time of writing, and resources, you could say, for how to unfold that—other kind of time—when they get home. I hope the participants return with full self and an active sense of possibility and joy.

“What can one learn about the body from writing the word? One of the things we can learn is that movement—typing, spinning, writing, leaping—is prayer.” ~ Elena Georgiou

______

Guest blogger and Pele’s Fire participant, Heather Leah Huddleston believes in the power of stories, that they are all nestled deep inside each person just waiting to be unleashed. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from Goddard College, and is also a certified yoga teacher and Nia white belt. When she’s not writing her own stories, or guiding others to theirs, you can find her staring intently, listening deeply to the rhythm of life, bending and stretching on a yoga mat, dancing through life barefooted, listening to music (mostly heavy metal), or cuddling a furry friend, all in the name of the wonder-filled world of story.

Ruth Ozeki is a critically-acclaimed filmmaker and novelist, and a Zen Buddhist priest. Her first two novels, the Kiriyama Prize winner

Ruth Ozeki is a critically-acclaimed filmmaker and novelist, and a Zen Buddhist priest. Her first two novels, the Kiriyama Prize winner