Apr 25, 2016 | Goddard, Random Thoughts, The Writing Life

I am not an expert on Prince. I do not own the purple disk of Purple Rain; I cannot sing every word of every B side. I have not analyzed the Purple One’s sexuality (except to rejoice that there was clearly enough of it for everyone) and have no insight into how or why he died. But last night at 4 a.m. in a club in Brooklyn, swaying to the final track in a five hour tribute set played by a D.J. who sang and cried and played air guitar the whole time, I was one of the grateful ones. Grateful for a man who stood in his truth and gave us permission to see our own.

I am not the first (not even in the top hundred) to observe that the power of Prince is that he showed us we could be and feel and want and do things that we didn’t know were possible, and that we could be bigger and more beautiful, more entirely ourselves, while doing it. It is a profound gift, but isn’t that what art is all about? The artist offers a vision of the world that comes from deep within, and the audience experiences themselves anew through that vision.

So what do Prince and my atypical clubbing have to do with writing? Nothing, really. But as a faculty member of the MFA in Creative Writing at Goddard College, my colleagues and I have been thinking about art, impact and transcendence, and so we have introduced a new slogan to try to capture who we are: Right for you. Write for the World. And in a moment when so many of us are re-experiencing the power of artistic connection in its sudden absence, it strikes me that it’s a lot like the way Prince chose to create.

Right for you. You decide why you come to Goddard, what you want to study, what you want to achieve, how you want to grow, and what you will walk away with. You know what you need (surely Prince said that), and Goddard is all about helping you get it. It’s more than creating your own study plan, picking your own books to read; it’s about letting the voice and stylistic choices of your project be your own. Goddard writers don’t graduate with a certain signature sound because we would rather play our own (thousands of) instruments. It worked for Prince, who said he refused his first record deal at age 15 because he could not produce himself. His highest trending quote on the Internet at the moment? A reminder that no one else can dictate who you are.

As writers, your uniqueness is also your power. Your experiences, your vision, your urgency, your empathy all combine to create a story that only you can bring to life. And that’s a very good thing when you consider that about one million books are published in the US alone every year. The story of you (which is, beneath all the layers, what even our most commercial or seemingly objective stories are) will attract others who didn’t know there was anyone else out there who shared their thoughts, imagination and experiences. Being true to yourself means resonating more precisely and deeply with your audience. Right for you translates into right for them.

Write for the World. We can spend years on our books, plays, movies, poetry collections. Whether a passionate essay on climate change or a young adult sci-fi thriller, we want to excite, entertain, motivate, and break as many hearts as possible. So writing for the world means finding your audience, and having the craft and skill to reach out and touch them in precisely the way you imagine, even if no one has ever done it that way, or some people aren’t into trench coats and underwear (though really, who wouldn’t be?).

Write for the World also suggests social consciousness: a responsibility to freedom, culture, equality, environment… Goddard’s mission is a radical one: one of human-centered, creative growth that comes out of, reflects, and responds to culture. Many students come to Goddard because of their interest in social justice and their personal politics, and for them, “write for the world’’ is a clarion call. “I am your conscious. I am love,” Prince sang. Shouldn’t the word be conscience, some might ask, defaulting to that moral assumption of right and wrong? But writing to protect and preserve and celebrate the world requires conscious awareness; as my son would say, “being woke.” Which is something else you can get at Goddard, but only if it’s right for you.

Let me know what you think of our slogan.

Dec 7, 2015 | Goddard, Our Nuclear Age, Random Thoughts, The Writing Life

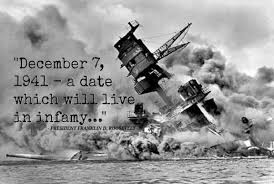

Today is a day that was supposed to live in infamy.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. response, kicked off a chain of events – including the internment and the atomic bombings – that still reverberate today.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. response, kicked off a chain of events – including the internment and the atomic bombings – that still reverberate today.

What do we know? President Roosevelt called Pearl Harbor an “unprovoked and dastardly attack” by a nation we were at peace with. Months after declaring war, Roosevelt deemed it “militarily necessary” to give the Secretary of War the power to control large segments of the country, and strip people of their citizenship, liberty and property (via Executive Order 9066), which resulted in the imprisonment of 120,000 American citizens and their Japanese immigrant parents. Three and a half years later, President Truman dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, calling the bomb “marvelous,” and “the greatest achievement of organized science in history.” He threatened the complete and rapid obliteration of Japan and promised “a new era” of atomic energy.

What if it was also common knowledge that before Pearl Harbor the US had imposed economic sanctions on Japan, frozen Japanese assets, and broken the Japanese diplomatic code? That two weeks before the attack, the Secretary of War (him again) wrote in his diary of efforts “to maneuver the Japanese into firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves”? Would we still believe that acts of war have no provocation?

What if schools taught these truths about the internment: that there was no evidence of spying, that it was the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership” for which the US government apologized, and that the Japanese Americans who volunteered to serve the US army out of the internment camps were some of the most decorated US soldiers in military history? Would we still have politicians today pointing to it as an example to emulate today?

What if the public knew that Japan had been trying to surrender for months before we bombed them to “save lives”? What if our government have not squelched the images of the devastation, or the very unmarvelous truth about radiation sickness – would we have detonated more than 2000 nuclear bombs since then? Would we be more aware of the fact that 75% of our nuclear power plants in the United States are leaking? That, four years after the disaster in Fukushima, Japan is still dumping tons of radioactive water into the Pacific Ocean, and it is now detectable in the water of the US coast?

History, as we have famously been reminded, is written by the victors, and alternate narratives are too often dismissed as conspiracy theories or beside-the-facts. My point in this history lesson is that we do know much more than the safe, comfortable sound bites that we choose to hang onto. We have actual images, diaries, records, declassified documents that prove that reality is more complicated that we allow it to be.

In his 1986 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Elie Wiesel reminds us of this truth: ”the world did know and remained silent.”

How does a writer “break the silence” when the facts are readily available, just ignored?

For me, this infamous anniversary is a reminder of how we choose not to hear, not to see, not to know, and most of all, not to learn from our mistakes. It is not a lack of information that hampers us, but a plethora that paralyzes us. As a result, we tend to come up with simplistic responses, and, at the same time, throw up our hands in despair at the complexity of the situation. We block each other out, refuse to listen; we let ourselves be led away from common ground. Silence, rhetoric, despair – all different ways to come up with the same response: nothing.

To police brutality. Gun violence. Racism. Environmental degradation and climate change. Redlining, redistricting, resegregating, restricting the vote. Limiting access to women’s reproductive healthcare. Closing our borders to refugees. The list goes on and on.

What do we do, as writers?

I don’t know. Do you?

At the Goddard MFAW residency in January, Douglas A. Martin and I are going to be initiating a discussion on resistance. We’ll see where it goes: What do we resist? How can we resist? How do we as writers take the information we have and shape an understanding? How do we change the narrative once and for all?

In the comments below, I invite you to share a “silence” that we know. Maybe if we each focus on just one, we can begin to understand the narratives that are spun to confuse and obfuscate; the falsehoods and tangents that encourage complacence. We can find ways to “interfere” rather than become “accomplices”:

“We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men or women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must — at that moment — become the center of the universe.” (Elie Wiesel)

*reposted from the Goddard MFAW blog: thewriterintheworld.com

Jan 21, 2015 | Random Thoughts, The Writing Life

Post State of the Union, the speech that is still sounding in my mind is one that was given back in November: Ursula Le Guin’s address at the National Book Award ceremony. Yes, she chided us for selling books “like deodorant,” but these are the words that are resonating in me:

“Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We’ll need writers who can remember freedom – poets, visionaries – realists of a larger reality.”

We will need writers who can remember freedom.

Chilling thought, especially in a country that purports to be founded on freedom. Our America was to be a new world where human rights were declared and held inalienable. And if that world, sadly, has never yet existed; if the gap between what we want to believe we are and how we actually act is huge and filled with death, torture, slavery, incarceration, brutality, poverty, inequity and fear…it is worth remembering that it was a pamphlet that helped spark the American Revolution: words on a page that conveyed a vision of freedom and individual worth so compelling that people gave their lives for it.

Chilling thought, especially in a country that purports to be founded on freedom. Our America was to be a new world where human rights were declared and held inalienable. And if that world, sadly, has never yet existed; if the gap between what we want to believe we are and how we actually act is huge and filled with death, torture, slavery, incarceration, brutality, poverty, inequity and fear…it is worth remembering that it was a pamphlet that helped spark the American Revolution: words on a page that conveyed a vision of freedom and individual worth so compelling that people gave their lives for it.

Le Guin reminded us that, “Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art.” Art, after all, is the manifestation of our radical imagination; our means of sharing our vision of a better world.

Writers: If you remember freedom and do not see it around you, start writing. Write about whatever feels urgent to you. It might be family or fantasy; it might be poetry or a post-apocalyptic dystopian TV show. Your truths will resonate, and you will go on record: contributing your vision, no matter how shrouded in metaphor, how personal, to the formation of our collective future. You are change: good or bad, loud or silent. Your choice matters. And if you write because you care and not to be the next best brand of deodorant; if you are fearless in your truths; you can change the world.

Speech excerpts: © 2014 Ursula K. Le Guin

Jul 26, 2013 | Random Thoughts

I met Moses last night on the streets in the West Village where he is living. He lost his leg and his mother when he was thirty five, and now he is over forty with a shiny prosthetic that hurts. He carries four small plastic bags of stuff. On the street, things get stolen. Moses used to work as a carpenter; he believes in compassion; and the server at the restaurant we walked into to get him a hamburger told him she would not seat him until I made it clear he was with me and I was buying. But then the manager came over and was very nice, and when I left, he thanked me for coming. Moses’s drink of choice was water. He is trying to get disability and social security and he has been denied, but he is still trying. His next hearing is on August 5th – my fiftieth birthday. So if you have some light and love to share that day, please send them to Moses.

Jun 7, 2013 | Goddard, Random Thoughts, The Writing Life

Once upon a time, when I was in a moment of artistic crisis, a dear, talented, compassionate and necessary writer told me this: “We write to clear a path in the forest that others may follow and then step off of to create their own paths.”

Today, on her blog, she writes, “What troubles me about rejections is that perhaps the audience I imagine for this work is not right, or doesn’t exist. Maybe I’m the only one interested in the things I write about. And if I am my only reader, then I don’t really need to write it, do I?”

Last night, I was reminded of the story of the Emperor’s new clothes, and how it takes only one small voice saying “Look at that man’s dinky!” to show us all, immediately, that we are being lied to. We ARE being lied to. The artist is the person who knows.

You are not your only reader, Elena. You are not the only one interested in identity and fitting in and cruelty and family and isolation and food and inheritance and war and trauma and equality and racism and freedom and love and all the other things you write about. We live in a society in which we all agree that Monday morning is the time we get up and go to work, and that work and what we get paid for it is the measure of our self worth. That is only an agreement – and a silly one at that – and we can change it anytime we decide to agree on something else. But without artists, we will never see the nakedness of our arbitrary collective decisions and make a change.

May 1, 2013 | Our Nuclear Age, Random Thoughts

We knew this was coming, but where do we go from here?

After dumping 11,500 tons of radioactive water into the sea within a month after the Fukushima meltdown began, in violation of international law, TEPCO continued to store a flood of radioactive water, assuming that – someday, somewhere – it could be cleaned and disposed of.

From the New York Times on Monday:

“Groundwater is pouring into the plant’s ravaged reactor buildings at a rate of almost 75 gallons a minute… A small army of workers has struggled to contain the continuous flow of radioactive wastewater, relying on hulking gray and silver storage tanks sprawling over 42 acres of parking lots and lawns. The tanks hold the equivalent of 112 Olympic-size pools.

“But even they are not enough to handle the tons of strontium-laced water at the plant …. In a sign of the sheer size of the problem, the operator of the plant, Tokyo Electric Power Company, or Tepco, plans to chop down a small forest on its southern edge to make room for hundreds more tanks, a task that became more urgent when underground pits built to handle the overflow sprang leaks in recent weeks.

“‘The water keeps increasing every minute, no matter whether we eat, sleep or work,’ said Masayuki Ono, a general manager with Tepco who acts as a company spokesman. ‘It feels like we are constantly being chased, but we are doing our best to stay a step in front.'”

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. response, kicked off a chain of events – including the internment and the atomic bombings – that still reverberate today.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. response, kicked off a chain of events – including the internment and the atomic bombings – that still reverberate today.