Dec 12, 2017 | Goddard, Hedgebrook, Shadow Child, The Writing Life

Last week I finished my first pass page proofs for Shadow Child, my new novel coming out in May. I started it in the year 2000.

Holding those pages in my hands, with their elegant design and their printing marks, I was amazed at how much effort has gone into the creation of this book, effort from people at the publishing house with whom I have become deeply connected and others I have never met. After almost two decades, my book has a face – the jacket I have attached here is brand new and just posted by Grand Central – and it’s a face that, as gorgeous and perfect as it is, is also one I could never have dreamed of. The birth of this book is much like the birth of a child, in that you imagine what your child will look like, but the person who was created in some magical and mysterious way from your DNA is both instantly recognizable and utterly unfamiliar.

Holding those pages in my hands, with their elegant design and their printing marks, I was amazed at how much effort has gone into the creation of this book, effort from people at the publishing house with whom I have become deeply connected and others I have never met. After almost two decades, my book has a face – the jacket I have attached here is brand new and just posted by Grand Central – and it’s a face that, as gorgeous and perfect as it is, is also one I could never have dreamed of. The birth of this book is much like the birth of a child, in that you imagine what your child will look like, but the person who was created in some magical and mysterious way from your DNA is both instantly recognizable and utterly unfamiliar.

It is taking a publishing village to get Shadow Child out into the world. At Goddard, when we write, we might imagine that we are done once the final draft is ready to send out into the world. This is not true. The draft that will be published, which had already been read in various stages by friends, writer friends, agents and editors, was so thoroughly…engaged with…by my brilliant editor that on some pages there were so many comments I literally had to take a deep breath, close the document and come back to it a different day.

As wonderful as my pre-publishing experience has been, we hit a snafu the other day when I turned in my acknowledgements and was told that they had only saved three extra pages for them, never expecting that I might need…eight.

I couldn’t cut the names of the people I interviewed, around fifty, even if my story changed and I didn’t use the material, and even if some of them have already passed on. I couldn’t cut the people who helped. I held onto the list of books that served as resources and inspiration because my novel is partly historical and the reader might want to know what really happened. Some of the decisions I made about how to use that history, what to identify, where to let go of fact in my quest for a greater truth – I felt that context was essential to include. And more than all of that, I could not cut my community.

Over two decades, the community around this book is vast, and I know that, as much as I tried to list my many supporters, by name and affiliation, there are perhaps an equal number of people who have not been named. This is because my brain is old, but also because the people who made a difference are not always the ones who read the whole manuscript or gave me feedback. They are my friends, my colleagues, the people I spent time with. They are my students who, in asking questions about their own work, sparked an answer to a problem I was having in my book for me. They are fellow travelers, Pele’s Fire writers who create an electric buzz of brainstorming around them wherever they go; listeners who insist that the passage I read cannot be cut, even if I have to reshape the novel to keep it there, or who remember a scene from six years before; friends whose comments on a piece of art we saw together, or a movie, crystalized an idea in my brain. We don’t always know where our ideas come from, or how they shift and change. There is a time when it is just us, and our muse. But there is a far longer time when we are writers in the world, and the others around us are collaborators and inspiration whether they know it or not.

I offered to drop my bio to accommodate the acknowledgements. They refused. They offered to compromise the internal design. I refused. We were able to move a few things around, and I got ruthless with my sentence structure to gain some pages, and so far, it looks like the acknowledgements are going to fit. They won’t be as long as a book two decades in the making requires, with apologies to anyone whose name I have forgotten.

My advice to you who are still writing? Jot down those names, make a note of the passing conversations. Seek out your community and cherish it. Never forget you are a writer in the world.

Feb 22, 2017 | Goddard, The Writing Life, Writing Advice

(reposted from The Writer in the World, the blog for the Goddard College MFA in Creative Writing Program)

On the plane headed to the Goddard residency in Port Townsend last week, I watched The Music of Strangers, a documentary about the international Silk Road Ensemble established by the cellist Yo-Yo Ma in 1998, but more than that, about the role of art in the world. One of the musicians, Kinan Azmeh, a refugee from Syria, spoke of watching his country in crisis: “I found myself experiencing emotions far more complex than I could express in my music. The music fell short. I stopped writing music. Can a piece of music stop a bullet? Can it feed someone who is hungry? You question the role of art all together.”

Since our election, I too have stopped writing. Everything I might say about what is going on around me has felt thin, and redundant. Anything I’d begun in the past seemed irrelevant and the act of continuing to write it – which requires turning away from the horror show of the news – vaguely disloyal and privileged. I have been living in a liminal space, making phone calls and going to community meetings and protest marches, while I wait for something to break open so that I can find my voice again.

Since our election, I too have stopped writing. Everything I might say about what is going on around me has felt thin, and redundant. Anything I’d begun in the past seemed irrelevant and the act of continuing to write it – which requires turning away from the horror show of the news – vaguely disloyal and privileged. I have been living in a liminal space, making phone calls and going to community meetings and protest marches, while I wait for something to break open so that I can find my voice again.

When I got to Goddard, I found, as always happens in a gathering of writers, that I was not alone. Although the theme for our residency was Risk and Revelation, it quickly became clear in the keynote presentations that our conversations would swirl instead around writing and resistance. My colleague Keenan Norris spoke of illiteracy as the “disastrous inability to describe what is before us.” Bea Gates spoke of “the need to unravel the horror before it unravels us.”

But it wasn’t until Keenan evoked Ralph Ellison’s comment that there is no peace in art but only “a fighting chance at the chaos of living” that I was reminded of the truth I already knew: the hate and violence, exclusion and separation that is currently imperiling our country is as old as recorded history, and it has always been my subject. It is the Japanese American internment my family endured; the dropping of two atomic bombs. Racism has been a part of us for centuries – in exclusion acts and Patriot Acts; redlining; prison for profit; slavery; colonization; outright theft of home and country. The difference now is not in degree but in speed. Thanks to the Internet, our world assembles itself out of a continuous pinging of tweets, posts, petitions, and action alerts that insist there may literally be no tomorrow if they are not immediately followed and shared. In her keynote, Bea talked about “Living inside a picture I could not see or read” and that was me: plucking what I could out of the torrent of scrolling insults, lies, jokes, leaks, and rumors, all conveyed in the truncated language of emoji and emotion, as if the world was at stake, and the right retweet would save it.

As Keenan reminded me by sharing the words of writers who have come before – Ellison, Hannah Arendt – the world is always at stake. And what’s more: “In art,” he said, “of course, each singular human life is the world— the world in a grain of sand.”

As Keenan reminded me by sharing the words of writers who have come before – Ellison, Hannah Arendt – the world is always at stake. And what’s more: “In art,” he said, “of course, each singular human life is the world— the world in a grain of sand.”

We writers traffic in the singular human life. My own books evoke racism, internment, bombings and trauma, through the choices, fears, actions and sacrifices of individuals. I interview people to create my worlds. I know myself well enough to know that everything I will ever write will begin with blood, breath, tears, joy, memory. Not as immediate as a tweet, in fact, just the opposite: writing from the body and visceral experience is quite a slow process, but perhaps it is no coincidence that creating a lasting society rooted in justice and humanity also takes time. So many of the readings we heard at the residency were prefaced by, “I wrote this [in some past moment in history] but it seems more important than ever now.”

With all of this so much on my mind, I facilitated a discussion for students and faculty to talk over where we, as writers, go from here. Borrowing from the post-it note explosion in the New York City subways after the election, we used a color-coded system to navigate the layers of our experience. The shock and awe of fake news and the fight or flight cortisol spikes of the resistance came out in the first two. That cleared some room for us to explore what matters most to us second two:

With all of this so much on my mind, I facilitated a discussion for students and faculty to talk over where we, as writers, go from here. Borrowing from the post-it note explosion in the New York City subways after the election, we used a color-coded system to navigate the layers of our experience. The shock and awe of fake news and the fight or flight cortisol spikes of the resistance came out in the first two. That cleared some room for us to explore what matters most to us second two:

1: WTF?!!? Say something. Get it out. Whatever blurt you are feeling right now, as a writer in the world, write it. (purple)

2: WHAT THE WORLD NEEDS NOW: What’s urgent, necessary, essential? (This is global.) (blue)

3: HOW ABOUT YOU? What are your own urgent themes, your preoccupations? What themes, situations and fears have you ALWAYS explored in your work? (yellow)

4: LOVE, LOVE, LOVE: Your essential heart. What do you care about? What moves you? What do you live for? (red)

The exercise took us through the stages of anger and fear, to sorrow, and then to love: where even our heartbeats slowed as we reconnected with what we lived for. That glorious and felt experience of living is, I believe, what our current climate of fast fear is trying to replace. The project was a powerful way to remind ourselves of the role of art, and the reason we write in the first place: to locate our humanity and make meaning.

I invite you to write your own post-its and add them virtually to our wall by sharing them in the comments on the Goddard MFA in Creative Writing blog: thewriterintheworld.com.

Apr 25, 2016 | Goddard, Random Thoughts, The Writing Life

I am not an expert on Prince. I do not own the purple disk of Purple Rain; I cannot sing every word of every B side. I have not analyzed the Purple One’s sexuality (except to rejoice that there was clearly enough of it for everyone) and have no insight into how or why he died. But last night at 4 a.m. in a club in Brooklyn, swaying to the final track in a five hour tribute set played by a D.J. who sang and cried and played air guitar the whole time, I was one of the grateful ones. Grateful for a man who stood in his truth and gave us permission to see our own.

I am not the first (not even in the top hundred) to observe that the power of Prince is that he showed us we could be and feel and want and do things that we didn’t know were possible, and that we could be bigger and more beautiful, more entirely ourselves, while doing it. It is a profound gift, but isn’t that what art is all about? The artist offers a vision of the world that comes from deep within, and the audience experiences themselves anew through that vision.

So what do Prince and my atypical clubbing have to do with writing? Nothing, really. But as a faculty member of the MFA in Creative Writing at Goddard College, my colleagues and I have been thinking about art, impact and transcendence, and so we have introduced a new slogan to try to capture who we are: Right for you. Write for the World. And in a moment when so many of us are re-experiencing the power of artistic connection in its sudden absence, it strikes me that it’s a lot like the way Prince chose to create.

Right for you. You decide why you come to Goddard, what you want to study, what you want to achieve, how you want to grow, and what you will walk away with. You know what you need (surely Prince said that), and Goddard is all about helping you get it. It’s more than creating your own study plan, picking your own books to read; it’s about letting the voice and stylistic choices of your project be your own. Goddard writers don’t graduate with a certain signature sound because we would rather play our own (thousands of) instruments. It worked for Prince, who said he refused his first record deal at age 15 because he could not produce himself. His highest trending quote on the Internet at the moment? A reminder that no one else can dictate who you are.

As writers, your uniqueness is also your power. Your experiences, your vision, your urgency, your empathy all combine to create a story that only you can bring to life. And that’s a very good thing when you consider that about one million books are published in the US alone every year. The story of you (which is, beneath all the layers, what even our most commercial or seemingly objective stories are) will attract others who didn’t know there was anyone else out there who shared their thoughts, imagination and experiences. Being true to yourself means resonating more precisely and deeply with your audience. Right for you translates into right for them.

Write for the World. We can spend years on our books, plays, movies, poetry collections. Whether a passionate essay on climate change or a young adult sci-fi thriller, we want to excite, entertain, motivate, and break as many hearts as possible. So writing for the world means finding your audience, and having the craft and skill to reach out and touch them in precisely the way you imagine, even if no one has ever done it that way, or some people aren’t into trench coats and underwear (though really, who wouldn’t be?).

Write for the World also suggests social consciousness: a responsibility to freedom, culture, equality, environment… Goddard’s mission is a radical one: one of human-centered, creative growth that comes out of, reflects, and responds to culture. Many students come to Goddard because of their interest in social justice and their personal politics, and for them, “write for the world’’ is a clarion call. “I am your conscious. I am love,” Prince sang. Shouldn’t the word be conscience, some might ask, defaulting to that moral assumption of right and wrong? But writing to protect and preserve and celebrate the world requires conscious awareness; as my son would say, “being woke.” Which is something else you can get at Goddard, but only if it’s right for you.

Let me know what you think of our slogan.

Mar 25, 2016 | Events, Goddard, The Writing Life

Dec 7, 2015 | Goddard, Our Nuclear Age, Random Thoughts, The Writing Life

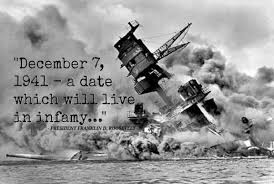

Today is a day that was supposed to live in infamy.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. response, kicked off a chain of events – including the internment and the atomic bombings – that still reverberate today.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. response, kicked off a chain of events – including the internment and the atomic bombings – that still reverberate today.

What do we know? President Roosevelt called Pearl Harbor an “unprovoked and dastardly attack” by a nation we were at peace with. Months after declaring war, Roosevelt deemed it “militarily necessary” to give the Secretary of War the power to control large segments of the country, and strip people of their citizenship, liberty and property (via Executive Order 9066), which resulted in the imprisonment of 120,000 American citizens and their Japanese immigrant parents. Three and a half years later, President Truman dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, calling the bomb “marvelous,” and “the greatest achievement of organized science in history.” He threatened the complete and rapid obliteration of Japan and promised “a new era” of atomic energy.

What if it was also common knowledge that before Pearl Harbor the US had imposed economic sanctions on Japan, frozen Japanese assets, and broken the Japanese diplomatic code? That two weeks before the attack, the Secretary of War (him again) wrote in his diary of efforts “to maneuver the Japanese into firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves”? Would we still believe that acts of war have no provocation?

What if schools taught these truths about the internment: that there was no evidence of spying, that it was the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership” for which the US government apologized, and that the Japanese Americans who volunteered to serve the US army out of the internment camps were some of the most decorated US soldiers in military history? Would we still have politicians today pointing to it as an example to emulate today?

What if the public knew that Japan had been trying to surrender for months before we bombed them to “save lives”? What if our government have not squelched the images of the devastation, or the very unmarvelous truth about radiation sickness – would we have detonated more than 2000 nuclear bombs since then? Would we be more aware of the fact that 75% of our nuclear power plants in the United States are leaking? That, four years after the disaster in Fukushima, Japan is still dumping tons of radioactive water into the Pacific Ocean, and it is now detectable in the water of the US coast?

History, as we have famously been reminded, is written by the victors, and alternate narratives are too often dismissed as conspiracy theories or beside-the-facts. My point in this history lesson is that we do know much more than the safe, comfortable sound bites that we choose to hang onto. We have actual images, diaries, records, declassified documents that prove that reality is more complicated that we allow it to be.

In his 1986 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Elie Wiesel reminds us of this truth: ”the world did know and remained silent.”

How does a writer “break the silence” when the facts are readily available, just ignored?

For me, this infamous anniversary is a reminder of how we choose not to hear, not to see, not to know, and most of all, not to learn from our mistakes. It is not a lack of information that hampers us, but a plethora that paralyzes us. As a result, we tend to come up with simplistic responses, and, at the same time, throw up our hands in despair at the complexity of the situation. We block each other out, refuse to listen; we let ourselves be led away from common ground. Silence, rhetoric, despair – all different ways to come up with the same response: nothing.

To police brutality. Gun violence. Racism. Environmental degradation and climate change. Redlining, redistricting, resegregating, restricting the vote. Limiting access to women’s reproductive healthcare. Closing our borders to refugees. The list goes on and on.

What do we do, as writers?

I don’t know. Do you?

At the Goddard MFAW residency in January, Douglas A. Martin and I are going to be initiating a discussion on resistance. We’ll see where it goes: What do we resist? How can we resist? How do we as writers take the information we have and shape an understanding? How do we change the narrative once and for all?

In the comments below, I invite you to share a “silence” that we know. Maybe if we each focus on just one, we can begin to understand the narratives that are spun to confuse and obfuscate; the falsehoods and tangents that encourage complacence. We can find ways to “interfere” rather than become “accomplices”:

“We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men or women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must — at that moment — become the center of the universe.” (Elie Wiesel)

*reposted from the Goddard MFAW blog: thewriterintheworld.com

May 2, 2015 | Goddard, The Writing Life, Writing Advice

While writing a recent response letter to one of my students, I found myself offering her advice that was also meant for me:

“Setting the scene, locating your character, revealing her motivations…that’s all discovery material just for you, the writer. Once you have discovered, then you can begin. When you are writing your drafts, start with emotion, put your character into turmoil, and add the action. Feel the difference?”

For me, the best part of teaching is remembering that we are all always learning, remembering, and beginning again. Happy writing!

Holding those pages in my hands, with their elegant design and their printing marks, I was amazed at how much effort has gone into the creation of this book, effort from people at the publishing house with whom I have become deeply connected and others I have never met. After almost two decades, my book has a face – the jacket I have attached here is brand new and just posted by Grand Central – and it’s a face that, as gorgeous and perfect as it is, is also one I could never have dreamed of. The birth of this book is much like the birth of a child, in that you imagine what your child will look like, but the person who was created in some magical and mysterious way from your DNA is both instantly recognizable and utterly unfamiliar.

Holding those pages in my hands, with their elegant design and their printing marks, I was amazed at how much effort has gone into the creation of this book, effort from people at the publishing house with whom I have become deeply connected and others I have never met. After almost two decades, my book has a face – the jacket I have attached here is brand new and just posted by Grand Central – and it’s a face that, as gorgeous and perfect as it is, is also one I could never have dreamed of. The birth of this book is much like the birth of a child, in that you imagine what your child will look like, but the person who was created in some magical and mysterious way from your DNA is both instantly recognizable and utterly unfamiliar.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. response, kicked off a chain of events – including the internment and the atomic bombings – that still reverberate today.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. response, kicked off a chain of events – including the internment and the atomic bombings – that still reverberate today.