Last week I finished my first pass page proofs for Shadow Child, my new novel coming out in May. I started it in the year 2000.

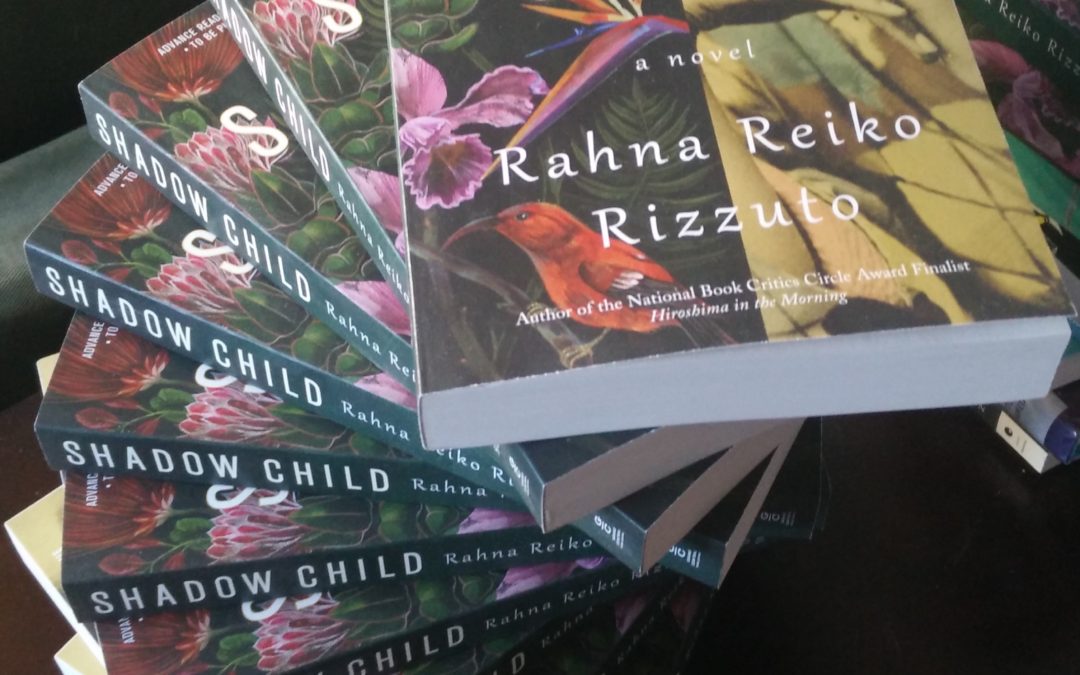

Holding those pages in my hands, with their elegant design and their printing marks, I was amazed at how much effort has gone into the creation of this book, effort from people at the publishing house with whom I have become deeply connected and others I have never met. After almost two decades, my book has a face – the jacket I have attached here is brand new and just posted by Grand Central – and it’s a face that, as gorgeous and perfect as it is, is also one I could never have dreamed of. The birth of this book is much like the birth of a child, in that you imagine what your child will look like, but the person who was created in some magical and mysterious way from your DNA is both instantly recognizable and utterly unfamiliar.

Holding those pages in my hands, with their elegant design and their printing marks, I was amazed at how much effort has gone into the creation of this book, effort from people at the publishing house with whom I have become deeply connected and others I have never met. After almost two decades, my book has a face – the jacket I have attached here is brand new and just posted by Grand Central – and it’s a face that, as gorgeous and perfect as it is, is also one I could never have dreamed of. The birth of this book is much like the birth of a child, in that you imagine what your child will look like, but the person who was created in some magical and mysterious way from your DNA is both instantly recognizable and utterly unfamiliar.

It is taking a publishing village to get Shadow Child out into the world. At Goddard, when we write, we might imagine that we are done once the final draft is ready to send out into the world. This is not true. The draft that will be published, which had already been read in various stages by friends, writer friends, agents and editors, was so thoroughly…engaged with…by my brilliant editor that on some pages there were so many comments I literally had to take a deep breath, close the document and come back to it a different day.

As wonderful as my pre-publishing experience has been, we hit a snafu the other day when I turned in my acknowledgements and was told that they had only saved three extra pages for them, never expecting that I might need…eight.

I couldn’t cut the names of the people I interviewed, around fifty, even if my story changed and I didn’t use the material, and even if some of them have already passed on. I couldn’t cut the people who helped. I held onto the list of books that served as resources and inspiration because my novel is partly historical and the reader might want to know what really happened. Some of the decisions I made about how to use that history, what to identify, where to let go of fact in my quest for a greater truth – I felt that context was essential to include. And more than all of that, I could not cut my community.

Over two decades, the community around this book is vast, and I know that, as much as I tried to list my many supporters, by name and affiliation, there are perhaps an equal number of people who have not been named. This is because my brain is old, but also because the people who made a difference are not always the ones who read the whole manuscript or gave me feedback. They are my friends, my colleagues, the people I spent time with. They are my students who, in asking questions about their own work, sparked an answer to a problem I was having in my book for me. They are fellow travelers, Pele’s Fire writers who create an electric buzz of brainstorming around them wherever they go; listeners who insist that the passage I read cannot be cut, even if I have to reshape the novel to keep it there, or who remember a scene from six years before; friends whose comments on a piece of art we saw together, or a movie, crystalized an idea in my brain. We don’t always know where our ideas come from, or how they shift and change. There is a time when it is just us, and our muse. But there is a far longer time when we are writers in the world, and the others around us are collaborators and inspiration whether they know it or not.

I offered to drop my bio to accommodate the acknowledgements. They refused. They offered to compromise the internal design. I refused. We were able to move a few things around, and I got ruthless with my sentence structure to gain some pages, and so far, it looks like the acknowledgements are going to fit. They won’t be as long as a book two decades in the making requires, with apologies to anyone whose name I have forgotten.

My advice to you who are still writing? Jot down those names, make a note of the passing conversations. Seek out your community and cherish it. Never forget you are a writer in the world.