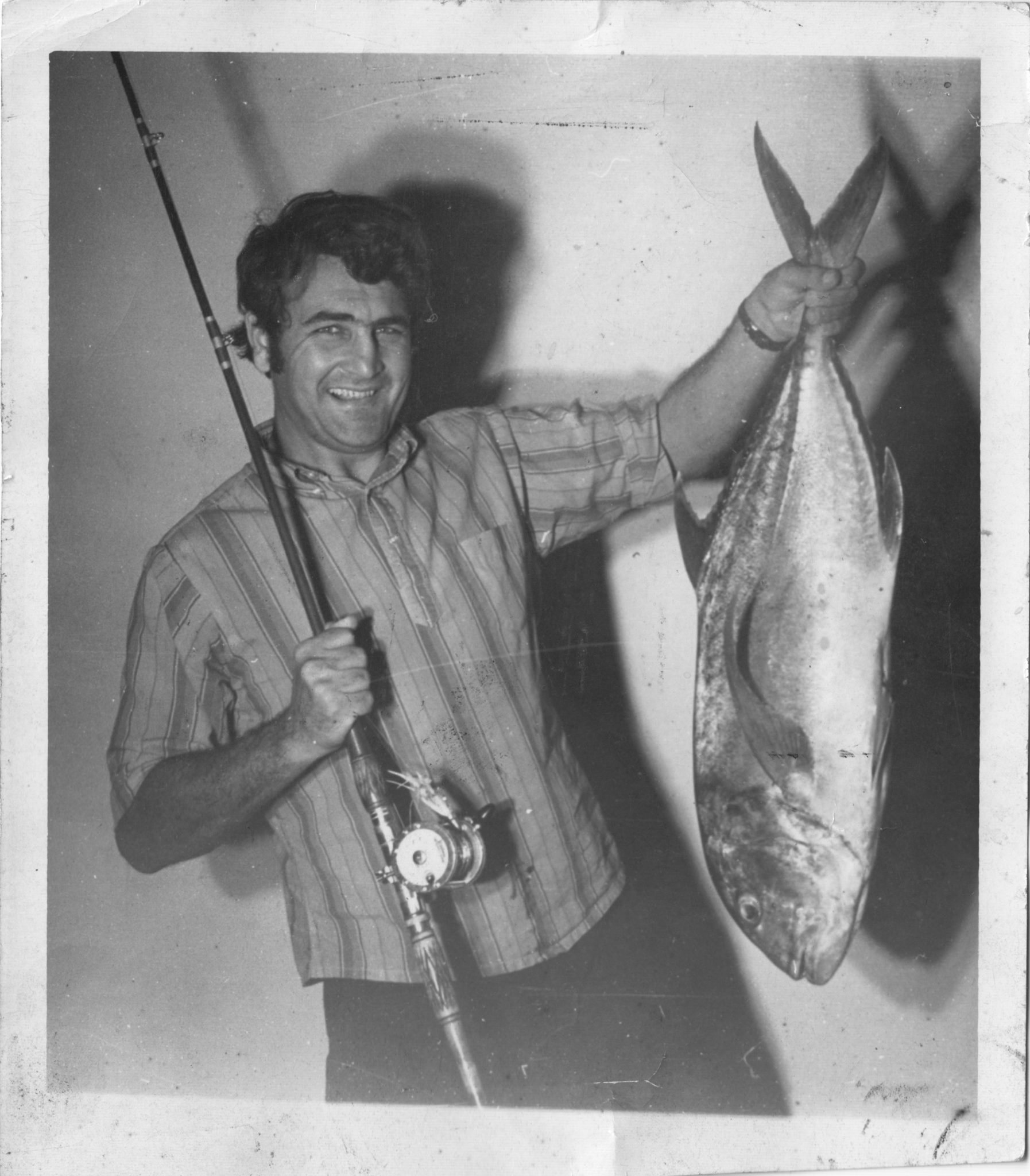

Although he didn’t lack for company, dad did sometimes go out alone. One of his favorite stories was the one about the quadruple ono strike. If I were a better storyteller, or perhaps a better daughter, I could tell you where he was exactly (my sons think between Black Point and Mahukona), and what he was trolling (Kai would bet he had his favorite red and black leadhead right down the middle). I can’t tell you what the weather was like, and which line went first. But what I can tell you is that he cut his hand pulling in the first ono and was bleeding all over the deck, with three more on. So he grabbed a towel (or was it a rag?) and wrapped it around his palm and tied it so he could get the other three into the boat.

You could find him on the Kailua pier by the King Kam every August during the Hawaii International Billfish Tournament where the marlin were being weighed. You could find him, just as easily, hanging out at Kawaihae, waiting for Flash to come in on his 14-foot skiff. He wanted to know what they caught, and he was full of questions: what, where, when, on which lure?

That is the stuff of his column, for sure, but he wasn’t gathering stories so he had something to write about. Just the opposite. He wrote because there were so many stories to tell.

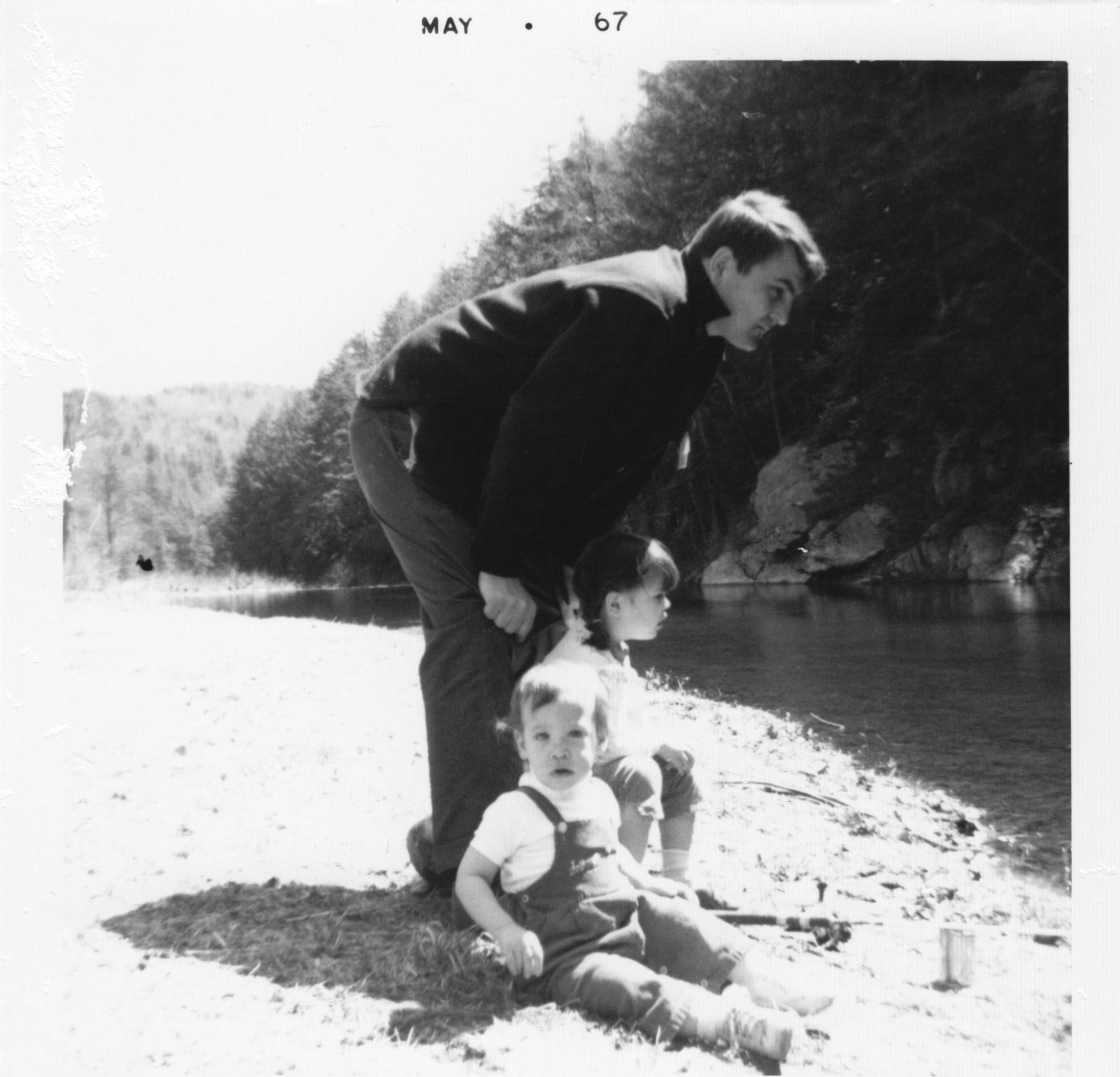

My father is known as an expert, a mentor, an educator, but I think of him as a student. In 1969, we had the good fortune of moving in next door to Zander Budge, who was running the Spooky Luki out of Kawaihae. Zander taught dad not only big game trolling, but also how to make lures.

Dad was a quick study. He absorbed anything anyone could teach him, and then tried to add his own spin. When he came to visit me in New York, he dragged me to Canal Street Plastics for flashy inserts and unusual skirt materials. The house was – and still is – littered with lures, from polished to gummy, and you could often find him wandering around sharpening hooks (which he had the habit of sticking his fingers with later).

As dad got older and we left home, he stopped taking the boat out as often. Even when the next generation of Rizzutos hit the water with him — including my son Kalei who insists that he pulled in the first and only black marlin ever caught on the Rizzuto Maru (he was 2), and my son Kai, who did in fact pull in a grander on the Ihu Nui when he was 16 (my brother says dad “just would not shut up about that!”) — you might believe that he had mostly stopped fishing.

But you would be wrong. Because, every Sunday, he was out fishing with all of you.

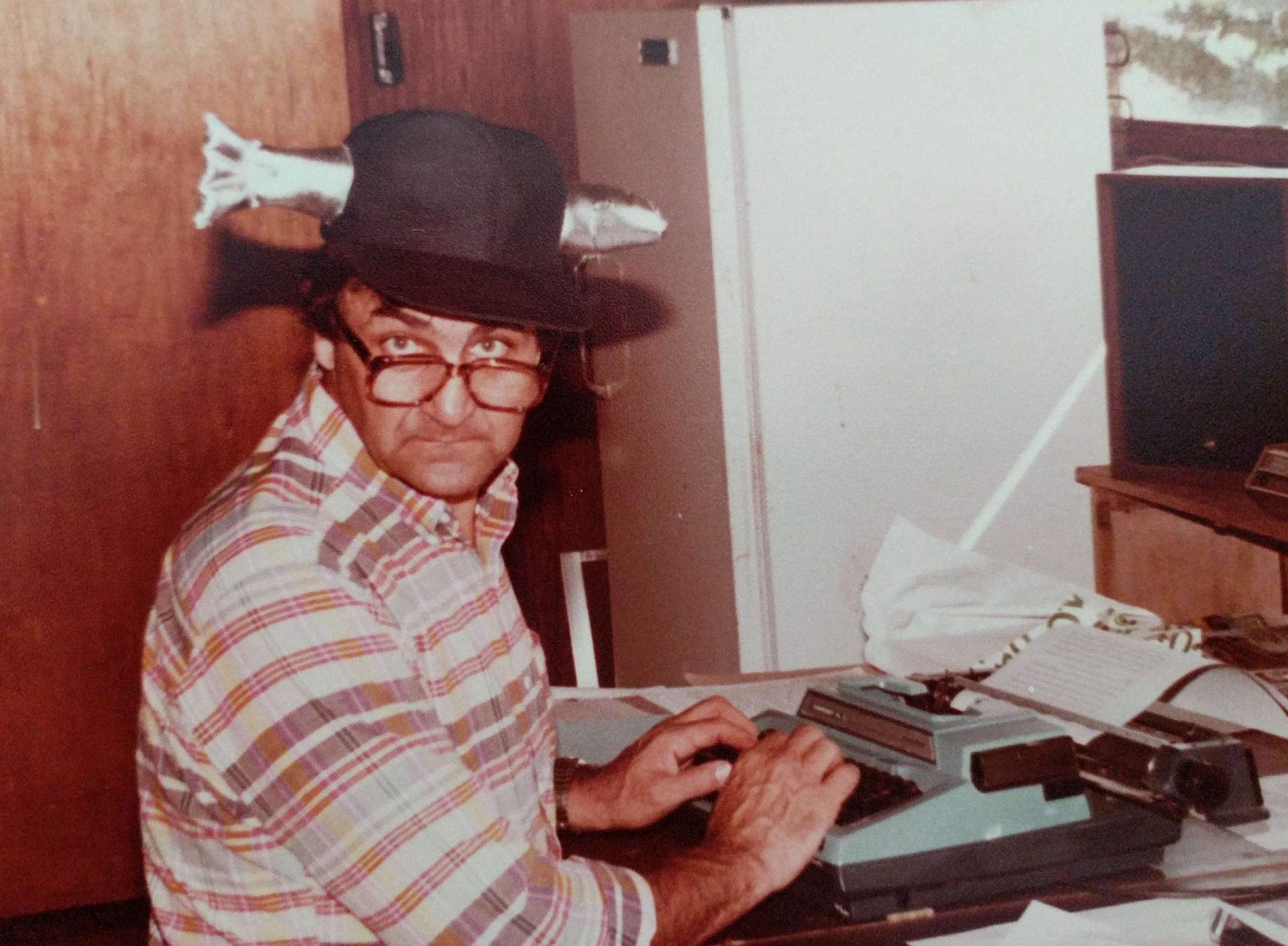

Sundays often found my father wandering back and forth between his office and the living room, stopping to gaze out toward to ocean. Some weeks, he’d been doing interviews and gathering stories for days already and now he was writing them in his mind.

Other times, he was waiting for the Charter Desk to call. You never failed him, and in your adventures, he found his own. Storytellers live in their heads, which is where all good fishing tales grow, so it was easy for him to join you. He was there when you pulled out of the harbor. When the fish hit. He knows what happened when it spotted the boat.

It doesn’t matter if you were in a kayak or a charter boat. Whether you caught a record, a wandering Spanish mackerel, or a baby sailfish the size of your palm. He could find you a cute title, a who-dunnit ending, an excuse to quote Emily Dickinson (“Hope is a thing with feathers”) because he was a fisherman, too.

I don’t think any of us understood just how sick dad was until he couldn’t write his column on Sunday, two weeks ago, which was doubly-upsetting because there was a tournament he had promised to cover and he hated to break his word. He passed the following week, in the early hours of Sunday morning.

It seemed fitting that his spirit chose Column Day to take off and go forever fishing with you.

This article first appeared in the West Hawaii Today, to announce my father’s passing and his celebration of life. Reposting here for Father’s Day.