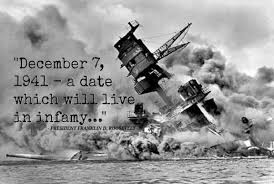

This Day, in Infamy and History

Today is a day that was supposed to live in infamy.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. response, kicked off a chain of events – including the internment and the atomic bombings – that still reverberate today.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. response, kicked off a chain of events – including the internment and the atomic bombings – that still reverberate today.

What do we know? President Roosevelt called Pearl Harbor an “unprovoked and dastardly attack” by a nation we were at peace with. Months after declaring war, Roosevelt deemed it “militarily necessary” to give the Secretary of War the power to control large segments of the country, and strip people of their citizenship, liberty and property (via Executive Order 9066), which resulted in the imprisonment of 120,000 American citizens and their Japanese immigrant parents. Three and a half years later, President Truman dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, calling the bomb “marvelous,” and “the greatest achievement of organized science in history.” He threatened the complete and rapid obliteration of Japan and promised “a new era” of atomic energy.

What if it was also common knowledge that before Pearl Harbor the US had imposed economic sanctions on Japan, frozen Japanese assets, and broken the Japanese diplomatic code? That two weeks before the attack, the Secretary of War (him again) wrote in his diary of efforts “to maneuver the Japanese into firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves”? Would we still believe that acts of war have no provocation?

What if schools taught these truths about the internment: that there was no evidence of spying, that it was the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership” for which the US government apologized, and that the Japanese Americans who volunteered to serve the US army out of the internment camps were some of the most decorated US soldiers in military history? Would we still have politicians today pointing to it as an example to emulate today?

What if the public knew that Japan had been trying to surrender for months before we bombed them to “save lives”? What if our government have not squelched the images of the devastation, or the very unmarvelous truth about radiation sickness – would we have detonated more than 2000 nuclear bombs since then? Would we be more aware of the fact that 75% of our nuclear power plants in the United States are leaking? That, four years after the disaster in Fukushima, Japan is still dumping tons of radioactive water into the Pacific Ocean, and it is now detectable in the water of the US coast?

History, as we have famously been reminded, is written by the victors, and alternate narratives are too often dismissed as conspiracy theories or beside-the-facts. My point in this history lesson is that we do know much more than the safe, comfortable sound bites that we choose to hang onto. We have actual images, diaries, records, declassified documents that prove that reality is more complicated that we allow it to be.

In his 1986 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Elie Wiesel reminds us of this truth: ”the world did know and remained silent.”

How does a writer “break the silence” when the facts are readily available, just ignored?

For me, this infamous anniversary is a reminder of how we choose not to hear, not to see, not to know, and most of all, not to learn from our mistakes. It is not a lack of information that hampers us, but a plethora that paralyzes us. As a result, we tend to come up with simplistic responses, and, at the same time, throw up our hands in despair at the complexity of the situation. We block each other out, refuse to listen; we let ourselves be led away from common ground. Silence, rhetoric, despair – all different ways to come up with the same response: nothing.

To police brutality. Gun violence. Racism. Environmental degradation and climate change. Redlining, redistricting, resegregating, restricting the vote. Limiting access to women’s reproductive healthcare. Closing our borders to refugees. The list goes on and on.

What do we do, as writers?

I don’t know. Do you?

At the Goddard MFAW residency in January, Douglas A. Martin and I are going to be initiating a discussion on resistance. We’ll see where it goes: What do we resist? How can we resist? How do we as writers take the information we have and shape an understanding? How do we change the narrative once and for all?

In the comments below, I invite you to share a “silence” that we know. Maybe if we each focus on just one, we can begin to understand the narratives that are spun to confuse and obfuscate; the falsehoods and tangents that encourage complacence. We can find ways to “interfere” rather than become “accomplices”:

“We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men or women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must — at that moment — become the center of the universe.” (Elie Wiesel)

*reposted from the Goddard MFAW blog: thewriterintheworld.com