Pop Sugar’s Best Books for Book Clubs, 2018

2018 Top Book Club Books to Read This Year, Book Bub

IndieBound | Apple | Amazon | Barnes & Noble

She is not supposed to be you.” READ MORE

shadow child

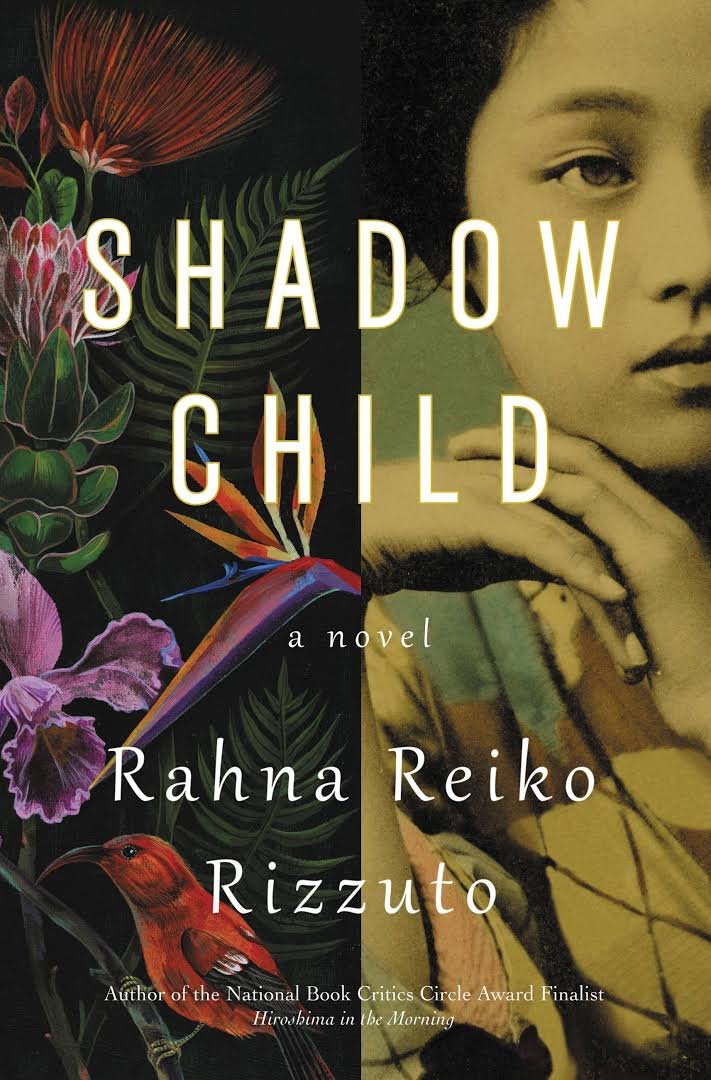

For fans of Tayari Jones and Ruth Ozeki, from National Book Critics Circle Award finalist Rizzuto comes a haunting and suspenseful literary tale set in 1970s New York City and World War II-era Japan, about three strong women, the dangerous ties of family and identity, and the long shadow our histories can cast.

Twin sisters Keiko and Hanako Swanson were so inseparable as children that they answered to a single nickname: Koko, made from “the small, safe endings left over when our mother created Kei and Hana, the bad girl and the good.” But who is the original, and who the shadow?

Growing up mixed-race and fatherless in a tiny Hawaiian town, Kei and Hana were raised in dreamlike isolation by their loving yet unstable mother. But when their cherished threesome with Mama is broken, and then further shattered by a violent betrayal that neither young woman can forgive, it seems their bond may be severed forever—until, six years later, Kei arrives on Hana’s lonely New York City doorstep with a secret that will change everything.

In her dazzling, suspenseful, and much-anticipated new novel, American Book Award-winning author Rahna Reiko Rizzuto takes us from the lush, treacherous shores of Hawai’i to the gritty streets of New York to the devastation of World War II Japan, exploring identity and destiny through the intertwined lives of three unforgettable women: Hana, Kei, and a Japanese-American orphan named Lillie who will find herself, time and again, on the dangerous cusp of history.

Bookended by two startling crimes, Shadow Child is a provocative, unsettling, and important read from one of the acclaimed masters of the form.

Reading Group Guide

- How do you think Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “strange and beautiful flower” speaks to Hana and Kei?

- Talk about the title of the novel. Does its meaning change for you, as a reader, over the course of the book?

- Lillie’s story is set against historical events. How does her very personal journey influence your understanding of those events? Does it influence how you see the significant events in your own world and your relationship to them? And, if so, how exactly?

- How does Lillie’s relationship with her parents affect her own role as a parent? Are there any echoes that stand out for you in the book?

- Do you consider Hana an unreliable narrator? Why or why not?

- Darkness plays a literal and metaphorical role in the novel. Discuss how it has impacted the characters, their life choices, and their relationships to one another.

- In the camps, Lillie objects to being “repatriated” to Japan: “Whatever world Donald had thought she belonged to when she married him, he was wrong. She was American. The preacher’s daughter. California was her home.” How do her feelings about her identity change?

- Hana is labeled the “good” twin while Kei is “bad.” Do you see this shift over the course of the novel? Why or why not? Is being the “good” daughter a blessing?

- The novel is written from many different perspectives: first person for Hana, third person for Lillie, and first, second, and first-person plural (“we”) for Kei. Why do you think the author made this choice? What effect do these shifts have on you, the reader?

- Names, and their meaning, play a large role in the book. Discuss what it means to give someone a name—is it simply a word, a label, or does it have a larger impact?

Revision: the long & winding road

This long and winding road to publication has also included a number of pitstops in the proverbial drawer. I wrote the first 100 pages in the year 2000, then went to Japan to research the character of Lillie, which led me to write a memoir instead. When I lost my way, either through terrible (though well-meaning) advice, or too much gusto for rearranging, I found my way back through the answer to a simple question: Why did I care about this story in the first place?

Reminding myself of what haunted me, and why it mattered, helped me anchor back into the personal, emotional journey of a family caught in the jaws of history.

Shadow Child explores questions of identity, motherhood, womanhood and sisterhood. It looks at how we inherit trauma, and how race and ethnicity influence how we see each other, and ourselves. And, sadly, it is timely: a reminder of America’s history as an immigrant country, and also of the human toll of war, and in particular, nuclear war. But at it’s heart – because that is what was in my heart – it is a journey through forgiveness, and an exploration of what we do for love.

locations

The same is not true of Hawai’i. There is a town that inspired the one I created here, where I did extensive interviews and research to catch the nuances of a certain life and time. However, unlike Lillie’s story, the story of the twins is in no way meant to be representative of that particular town or its people. Hawai’i is a rich and diverse place, and it requires many voices to bring it to life. Much like the conflicting accounts I heard during my interviews about the tsunami, the beauty of Hawai’i is that no two stories will be the same. To encourage the reader to read more about Hawai’i, and to explore the many local authors who are writing from their indigenous, multicultural, and diverse experiences, I chose to leave my fictional town unnamed.

RESEARCH

Some of the written sources I leaned on most heavily include: And Justice For All: An Oral History of the American Detention Camps, John Tateishi (Random House, 1984); Dear Miye: Letters Home from Japan, 1939-1946, Mary Tomita (Stanford University Press, 1995); Hibakusha: Survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ed Gaynor Sekimori (Kosei Publishing, 1986); Hiroshima Diary, Michihiko Hachiya (University of North Carolina Press, 1995); Our House Divided: Seven Japanese Families in World War II, Tomi Kaizawa Knaefler (University of Hawaii Press, 1991); Personal Justice Denied; Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, (University of Washington Press, 1997); Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in World War II, Roger Daniels (FSG, 1993); Unforgettable Fire: Pictures Drawn by Atomic Bomb Survivors, ed. Japan Broadcasting Corp (NHK) (Pantheon, 1977); Were We The Enemy?: American Survivors of Hiroshima, Rinjiro Sodei (Westview Press, 1998); Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps, Michi Weglyn (Morrow, 1976). I also consulted the Japanese American National Museum; the UCLA Asian American Studies Center, and their publication, The Amerasia Journal; the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley; and the Hiroshima Peace Museum, among others.

And if you are curious about what really happened during the tsunamis that have affected Hawai’i over the years, I recommend Tsunami! by Walter C. Dudley and Min Lee (University of Hawaii Press, 1998), and a trip to the Pacific Tsunami Museum in Hilo, which offers extensive oral histories, archives, scholarship and science.

READ MORE HAWAIIAN AUTHORS

As such, there are many Hawai’is. To get you started, I refer you to Honolulu Magazine’s 50 Essential Hawai‘i Books You Should Read in Your Lifetime, described as the “first-ever list of the most iconic, trenchant and irresistible island books, as voted by a panel of literary community luminaries.” It includes Foundational Texts, History & Social Criticism, “Lucky We Live Hawai‘I” biographical texts, Novels & Short Fiction, and Poetry. Not a cannon, or a ranking, but a resource; it gives a special nod to the “consciously local, provocative writing” of writers telling their own stories.

The top vote-getter for Honolulu Magazine’s list was Lois Ann Yamanaka, whose books Wild Meat and the Bully Burgers and Heads by Harry, are set in Hilo, where she grew up (and which is also the town that inspired Shadow Child). Yamanaka is the award-winner writer of quite a few books set in different parts of Hawaii, including her first book, a poetry collection called Saturday Night at the Pahala Theater published by Bamboo Ridge Press in 1995. Bamboo Ridge is a terrific place to start to find authentic local stories: a local, nonprofit publisher that was founded in 1978 to “publish literature by and about Hawaii’s people.” Also included in its catalog, three other books set in Hilo in earlier days: Susan Nunes’s A Small Obligation and Other Stories of Hilo (1982), and Juliet Kono’s Hilo Rains (1988) and Tsunami Years (1995).

Reiko ANSWERS YOUR QUESTIONS

In my first two books, I found myself exploring how memories shape us, and also the role of secrets and silences, and how we can inherit trauma, even when that trauma is unspoken. These themes are very central to Shadow Child as well. I was interested in telling the story of Hiroshima. I was interested in exploring sisterhood, and thinking about how we create our own identities against the pull of others and against a world that wants to tell us who we are. I was also haunted by a terrible moment of violence that happened to a friend of mine, and the way that moments like that can reverberate and mark even those on the periphery.

You were born and raised in Hawaii. How does that inform the book?

When I was growing up, Hawai’i was a world apart from “the mainland” as we called it. We didn’t have TV reception until I was fifteen; and, when we did, they aired shows two weeks late (the time it took to ship the tapes to the islands). There was a certain rhythm to life there, a certain connection to the land and ocean, and a connection, too, to community. It was also a multicultural place, rooted in generosity and the concept of ‘ohana. Hawai’i infuses you; you can recognize someone else from Hawai’i anywhere else in the world. And, in that way, I think Hawai’i has made me who I am and is in every book I write.

Did the novel take unexpected turns as you were writing it, or did you know from the beginning where you were headed?

This novel twisted and turned and stood on its head for almost two decades. I knew how it began, who the twins were, and the outline of their story and Lillie’s. But it was two books when I started. The twins’ story was half done, and I went to Hiroshima to research Lillie’s story. As I said in my acknowledgements, the shape and tone of the story kept changing, even the genre (on advice of an editor, I tried my hand briefly at making this a thriller). As for the characters, I would say they didn’t change so much as reveal themselves, and express themselves in ways that I didn’t expect but were true to who they were. So every time I discovered something new about them, it was like, “Aha! There you are!”

What was your research process like?

All of my books have been very exhaustively researched. I use historical documents—facts, if you will—but I also interview people, who have wildly different recollections and experiences, sometimes of the same event. I am interested in little details about life: favorite clothes, particular smells, funny anecdotes. I am also interested in what is forgotten. For example, in researching the actual tsunami that inspired the one in my book, I found people who remembered the scientists on the bridge, and others who swore there were no scientists there. I found a written documentation of the scientists, so I put them in my novel. But facts and truth can be very different things, and that comes out starkly, especially when you are dealing with traumatic memories as I often am.

Lillie’s story is inspired, in part, by stories from your own family. How did the decision to treat this subject in fiction, rather than reportage, change your understanding of or relationship to that history?

My family members lived through the Japanese-American incarceration, fought in the war, worked for the American Occupation, and witnessed the devastation of the Hiroshima bomb. But those stories were largely lost to silence. In my writing, I am trying to fill those silences, and understand the experiences that shaped us—that shaped me, even though they were unspoken. Fiction allowed me to feel the effects and consequences of history, rather than just compiling and understanding the missing facts.

What are you working on next?

I have a draft of a young-adult fantasy novel, which is currently marinating in a drawer, and a couple of story ideas in the “suspenseful literary fiction” genre. I’m going to let them battle it out and see which one wants to come next.